[Action learning] is a way to grow ourselves internally, to live into the vision in alignment with our values, and in line with what we are doing with our partners and clients to change the world.

Elissa Sloan Perry

Action learning is a process of asking questions, undertaking rapid experimentation, reflecting on the outcomes, and modifying practices based on the results. According to the World Institute for Action Learning, “action learning is a process that involves a small group working on real problems, taking action, and learning as individuals, as a team, and as an organization. It helps organizations develop creative, flexible, and successful strategies to pressing problems.”

At MAG, our staff and consultants have long been boosters of action learning. Our practices have grown from conversations amongst ourselves, our partners, and our clients; we have undertaken these conversations with the aim of finding ways to continually modify how we’re interacting with the rapidly changing environment that surrounds us. Now, not only do we advocate that others undertake action learning processes, but we have committed ourselves to practicing what we preach. Although this has not always been easy, it has tremendously enriched our organization. As MAG Co-Director Elissa Perry states, the organization’s adoption of action learning is important because “it is a way to grow ourselves internally, to live into the vision in alignment with our values, and in line with what we are doing with our partners and clients to change the world.”

In the process of shifting our internal culture to embrace transformative practice more fully, we adopted three mutually supportive areas of emphasis: First, we focused on pathways for everyone to meaningfully participate in action learning processes; second, we embraced a cycle of experimentation and reflection; and third, we committed to surfacing and directly addressing our differences.

So what have these practices looked like up close?

1. Supporting Everyone to Meaningfully Participate in Action Learning

A central part of action learning at MAG is treating everyone — clients, partners, all staff, and board — as partners in the process of experimentation and reflection toward a future rooted in dignity, justice, and love.

As one example, we endeavored to put this idea into practice as we developed a new vision and identified the most critical elements needed to make this vision a reality. Instead of merely hashing things out in a high-level board retreat, we challenged ourselves to reach farther. We received feedback from clients, partners, and participants in our learning projects—who shared what they learned was needed for successful movement building.

We also brought staff and board members together through a series of meetings and retreats. And we prepared operations staff to participate in the conversation by sharing our guiding questions in advance and coaching them to apply their wisdom and experience to these questions.

This effort to ensure that multiple people could participate yielded concrete benefits. For example, our finance manager offered a compelling metaphor for MAG’s role: a “waterwheel” connecting people, ideas, and resources across an expanded justice ecosystem and building power from that current.

2. Taking an Experimental Stance

Before fully committing to a new vision for our organization, we implemented other action-learning processes as well. We set up benchmarks to test our new directions before we fully committed to them. For each benchmark, we created discrete experiments for learning.

Over a three-month period, for example, we focused on the following benchmark questions:

- Could we turn lessons from MAG’s existing practices into materials that we could share publicly?

- Could we find ways to collaborate with other capacity builders to strengthen movements?

- Could we create internal systems to support integration of learning, partnerships, and consulting?

- Could we hire and “on-board” new staff to expand our work?

Using a design-thinking process, we came up with dozens of possible actions we might pursue. We then narrowed the lists and tested one to three ideas in each area, with clear benchmarks for success. Focusing on these objectives and launching experimental initiatives around them allowed us to take abstract organizational goals that might ordinarily have been deferred and turn them into exciting areas of internal collaboration.

In the end, the process resulted in many changes in how we do our daily work. These include revised accountability structures, cross-functional task teams, new communications content, and collaborative work and learning with partner organizations. We emerged from the process excited about more deeply integrating action learning into new cycles of experimentation and organizational growth.

We continue to use this experimental approach as a means of both stepping back to reflect on strategic questions and finding more collaborative and effective ways of working. Running new experiments in six-month cycles keeps our feedback loops short. It helps us quickly discern what’s working and what we need to try differently.

Through this ongoing process, we are currently pondering a number of valuable questions:

- How can we further change organizational patterns to create more space for intentional reflection? In response, we have developed a 30-question framework for ongoing reflection on the interconnected areas that make up our work.

- How can we use collaborative technology platforms to enhance (but not replace) our ways of working? To this end, we are testing a range of platforms, such as Zoom, Asana, and Slack.

- How can we identify and adopt different work strategies to support our organizational goals of treating people as whole beings? In response, we have experimented with different time tracking methods and flexible work schedules.

3. Leveraging Our Differences

At MAG, our differences are an organizational strength and source of generativity. With a culture of learning and practice, each of our staff members are willing to take the risk of expressing a different point of view, and they are willing to shift their perspective based on listening to others.

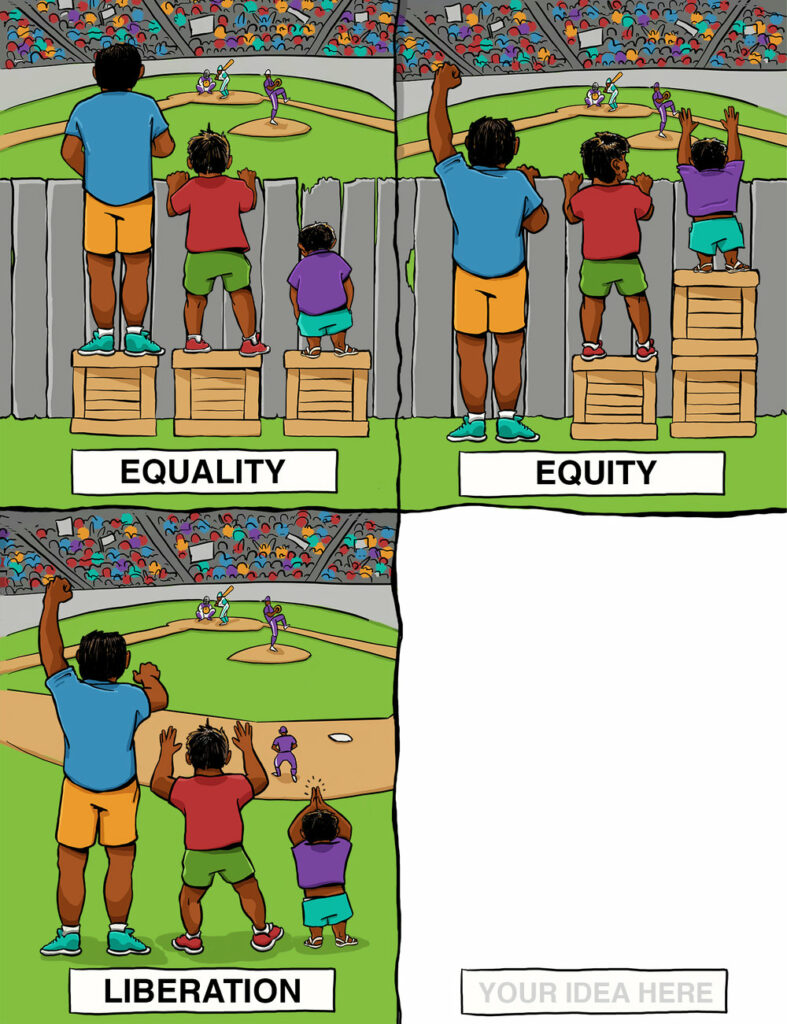

For instance, MAG’s staff has challenged itself to engage in difficult conversations about equity. As we discussed what equity meant for MAG, there were differences of opinion about what it would take to achieve liberation. We discussed many of the questions that come up for our clients when they engage in equity, race, and liberation work: Why is racial equity front and center at this time? How is this consistent with embracing all aspects of people’s whole selves, including gender, class, religion, caste, and other categories?

To inquire into this question, staff members have held conversations about what we have learned from our personal lives, from our work as consultants and activists, and from our formal training. We have provided access to trainings and other learning opportunities that would help us advance on our personal journeys around race. And we engaged facilitators to create space for us to advance this conversation as a group. Without a culture of learning, we would not be able to have this challenging discussion about race and its intersection with other elements of equity. And, because we are learning together, we were ready to hold each other in the pain and meaning making that came after the election.

Leadership Creates the Space for Instructive Failure

In many organizations, learning stops with the decision to do something. With a culture of action learning, we engage a range of people at regular intervals in reflecting on what we are learning about specific questions with clear benchmarks. This practice makes us accountable to ourselves, to each other, and to our vision. It also provides valuable information about everything we do—from our business model to wellness strategies to communications platforms. With this approach, for example, we have developed new policies to support flexible time, we have changed systems to be less burdensome, and we continue to reflect on and generate experiments to improve personal sustainability.

MAG’s experiences with action learning reflect a variety of insights highlighted in the literature of organization development. Adopting a culture of experimentation, reflection, and change through action learning can be part of a larger commitment to making your institution a “learning organization.” Research on such groups has shown that three broad factors make the difference in allowing for increased organizational adaptability: a supportive learning environment (including appreciating differences, openness to new ideas, and time for reflection), the implementation of concrete practices and processes, and leadership that not only supports new practices but models them.

Leaders committing themselves to action learning make it safe for others to try new things. Too often, people with limited formal authority restrict themselves (or feel restricted) from offering new ideas or alternative perspectives. They worry that a mistake will lead to reprimand. Leaders who want to create intentional learning organizations can work to address this not only by encouraging small, low-risk experiments, but—perhaps more importantly—by reframing failure as a source of learning.

No doubt, our process of implementing this change in culture and practice at MAG hasn’t been flawless. But we have been humbled by the positive results of the experiments that we’ve challenged ourselves to undertake, and we look forward to applying our learning internally, in our client work, and in our collaborations with partner organizations.

Banner photo credit: James Emery | CC BY 2.0