As MAG staff continuously deepens our own learning and practice in the five elements that we believe are critical to a thriving justice ecosystem, we will be sharing more from our individual learning journeys alongside other kinds of learning. In this blog, Amy B. Dean shares her personal and continuing learning journey regarding the relationship between race and class in advancing equity.

Why Colorblind Efforts to Address Economic Injustice Do Not Go Far Enough

As someone who has worked for more than two decades in pursuit of economic justice, I have seen first hand how issues of race and class in America are inseparable. I firmly believe that attempts to address economic exploitation that do not recognize how racial divisions are deeply sown into the fabric of our working lives are bound to fall short.

As a Jewish woman who was raised in a class-first context and spent many years in the labor movement, I have lived a process of coming to understand the limits of aspiring to a universal class politics, free of concerns about “identity.”

Over the course of my career, I’ve come to a deepening appreciation of the importance of race. This hasn’t meant abandoning class. But it has involved growing to realize how colorblind appeals to unity among working people are inadequate.

Allow me to explain what I mean.

Growing Up With a Class-First Lens

In my grandparents’ home, when you walked into the foyer, you saw there was a picture of a strange man hanging on the wall.

When I was a young girl, I wondered if this might be a far-off relation whom I had never met. It wasn’t until I was a bit older that I learned that the man in the picture was Walter Reuther, the legendary labor organizer who led the United Auto Workers from the 1940s to the 1960s.

For my grandparents, this portrait was an interesting choice. They had never worked in an auto factory or belonged to the UAW. Having immigrated from Eastern Europe as children with their Jewish parents, my grandfather became a full-time musician and my grandmother a costume-maker for the theater. Proud members of the unions in their fields, it didn’t matter to them that Reuther came from a different industry. He was a champion of social justice and the rights of working people.

My other set of grandparents were socialists, and they were also first-generation Jewish immigrants. For them, socialism was rooted in class analysis, but it represented a vision of a better world for everybody, regardless of race or social position. It was a type of colorblind, universalist populism that imagined a world more equal and free.

But even as a small child coming up in this class-conscious setting, I began to realize that colorblindness had serious limits. For, in fact, race played a huge role in shaping patterns of injustice in the world around me. I grew up in Hyde Park, a neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. By the time I was born, the Supreme Court had banned racially restrictive housing covenants, and Hyde Park had become a multi-racial neighborhood. Yet all around us was a sea of Chicago segregation. I grew up with a gut sense of how systemic manifestations of prejudice could create deep fear and hostility in communities.

My family instilled in me a belief in racial and economic justice. But it also left me with a lot of growth and maturation to do. Many of the kids I grew up with in my multi-racial neighborhood were children of doctors and lawyers. This helped to create for me a sense that, if economic oppression could be alleviated, race might somehow disappear. The default belief among many white organizers I knew when I began my professional life was that, if everyone joined a union, it would lift everyone’s wages and racial differences would not pose a problem–that somehow racial frictions were mostly dependent on class inequality.

I always knew that this position was not wholly tenable, but it took living though a number of other experiences to show me how.

Economic Justice Without Colorblindness

By moving beyond a colorblind notion of class and seeing race as a critical force in shaping how economic relations were structured, labor overcame limitations in policy and outlook that had hampered its ability to organize and represent all working people.

Inspired by my grandparents I began a career in the labor movement, where I would work for more than two decades as an organizer, researcher, and elected leader. There I quickly saw how, when we treated race as a “side issue,” we too often failed to secure the economic justice we sought. I learned that, by explicitly addressing race, rather than sidestepping or denying racial injustice, it made us into a stronger movement.

In the late 1980s I worked for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU). I loved the union, but I was struck by a disjuncture. While the membership of the union was predominantly Black and Latino, with large numbers of women represented, the top leadership of the union was made up entirely of White guys. This did not sit well with me or with other women and people of color in the organization. To their credit, although the union’s leaders could be slow to take decisive measures, they did see that change was needed. One area in which they pushed this change forward was on the issue of immigration. I was tasked with creating the union’s first legalization program for members who were immigrants, helping with citizenship and green card processes, family reunification, and other legal support. Acknowledging that our union was built by an earlier generation of immigrants, we committed ourselves to honoring this legacy by recognizing people of color who had arrived in the country more recently as a central part of our membership.

My work around this issue continued after I moved to California and became head of the AFL-CIO’s Central Labor Council in Silicon Valley. At that time, in the late 1990s, I was part of a cross-union group of labor activists that worked to push through a crucial shift in the AFL-CIO’s stance on immigration. For decades, the federation’s official position blamed immigrant workers for depressing wages and taking jobs. But, in February 2000, with pro-immigrant unions in the lead, the AFL-CIO changed its position to support amnesty for all undocumented immigrants. It took a lot of grassroots organizing for our team of activists in the movement to convince our union brothers and sisters that this was the right way to go. But we had seen too often how employers were able to exploit the vulnerability of undocumented workers to the detriment of the entire workforce. Likewise, we saw how they were able to use racial divisions and scapegoat immigrants to disguise their own role in suppressing wages and creating unsafe working conditions.

By changing its policy, the AFL-CIO was able to move from a position that stoked racial division to one that encouraged solidarity across differences. By moving beyond a colorblind notion of class and seeing race as a critical force in shaping how economic relations were structured, labor overcame limitations in policy and outlook that had hampered its ability to organize and represent all working people.

This change in policy reflected a wider change in the composition and complexion of organized labor. Working with unions in California, I learned that successfully fighting for economic justice was not possible without an understanding of how race and class intersect. Historically, the stereotypical image of the “working class” in the United States—and the stereotype of a typical union member—is that of a White man in a hard hat. This image was always a very partial and problematic representation of working people in our country, but it arguably had some salience to the male-dominated industrial workforce of the 1940s.

However, in California in the 1990s, it was clear that a vision of a vibrant and resurgent labor movement would need to be based on a fundamentally different set of images, ones that highlighted the key roles of women and people of color as leaders in their workplaces.

Even though I was in Silicon Valley, whose public image revolved around high-paying tech jobs, the truth is that the fastest-growing job classifications were in the service sector. They included nurses, janitors, office support staff, retail cashiers, and food service workers. Members of these professions became key leaders in our movement, projecting a new sense of what a rebellious labor and working-class identity could look like. Many of them were Latina women. They pushed us to connect issues that went beyond the workplace. In 2001 we were able to pass a major child health initiative through the city and county government, which provided health coverage for tens of thousands of low-income children, including immigrant children, regardless of legal status. The measure became a model for state-level initiatives in California and beyond. We also made important advances around transportation and affordable housing in the San Jose area.

When we were able to succeed, it was not by ignoring difference and appealing to a universal class consciousness—“you are all being exploited by the same bosses.” In the past, that approach had led to a union leadership that was predominantly white and overwhelmingly male, one focused on preserving past gains and unable to understand why its appeals were not resonant in today’s workforce. Instead, our success was based in recognizing how the lived experience of class had a very racialized character, reflected in segregated neighborhoods and in public health outcomes that varied greatly based on race. Our movement made progress when we acknowledged these realities, and elevated leaders who had experienced the interplay of race and class in their daily lives, and offered a path forward, articulating how groups who saw themselves divided by lines of race did better when they came together across their differences.

In some ways, the goal was much the same as that of colorblind class universalism—a society of greater fairness, equality, and solidarity. The difference is that the new approach highlighted how a colorblind outlook itself made the achievement of this goal unattainable. A rising tide for the working class, fostered by a strong labor movement, could lift all boats, but it lifted these boats very unequally when it floated only on universalist currents. True justice and equity required an honest and explicit acknowledgment of overlapping forms of oppression.

How Identity and Class Politics Intertwine

We think a different approach is necessary, one that links, rather than counterposes, class and race. The progressive movement should expand from a vision of racism as violence done solely to people of color to include a conception of racism as a political weapon wielded by elites against the 99 percent, nonwhite and white alike.

Heather McGhee and Ian Haney-López

In the past decade, I have been hopeful that such lessons would be widely appreciated and would serve as guiding principles in progressive politics. Unfortunately, the 2016 election and its aftermath have seemed to amplify an unproductive debate that sees efforts to address race and class as at odds, instead of exploring their necessary interrelation.

During the Democratic primaries Heather McGhee, president of the think tank Demos, and Ian Haney-López, a law professor at U.C. Berkeley, recognized the danger of this emerging trend and offered an important intervention. They argued against those who viewed seeing a race-conscious agenda as a liability for movements seeking to engage with a wide swath of working people in America. “We think a different approach is necessary,” they wrote, “one that links, rather than counterposes, class and race. The progressive movement should expand from a vision of racism as violence done solely to people of color to include a conception of racism as a political weapon wielded by elites against the 99 percent, nonwhite and white alike.”

McGhee and Haney-López challenged “white economic populists to take up the race conversation with white voters, by directly addressing racial anxiety and its role in fueling popular support for policies that hand over the country to plutocrats.” The goal here was not to abandon class politics. Rather, it was to see how, at least since the 1970s, conservatives have used dog-whistle appeals to racial prejudice to fuel attacks on the New Deal social contract. By painting people of color as the undeserving beneficiaries of this previous contract, the right was able undermine unions, eviscerate job standards, and defund public institutions that bolstered working people as a whole.

Rather than calling out this racist strategy, too many progressives turned to lamenting how paying attention to race is unduly divisive. Putting aside the moral imperative of confronting racism, there is a fundamental strategic flaw in their reasoning. It is true that racial division is an impediment to working-class unity. But the fact that race divides us should be reason for us to attend to it with more care and diligence, not to ignore it. Rather than encouraging us to adopt a colorblind appeal to class unity, it should give us further motivation to understand how racial appeals are central to perpetuating economic exploitation.

During my time in the labor movement and after, I have been fortunate to be in conversation with Bill Fletcher, past president of TransAfrica Forum and former Assistant to AFL-CIO President John Sweeney. In the wake of Trump’s election, Fletcher sagely wrote, “There is an unfortunate belief among many progressives that class politics is about economics in a narrow sense. Thus, a demand against Wall Street and its elite is considered class politics. A Chicano demand in the Southwest for land redistribution or the protection of long-held Chicano land rights is frequently described as identity politics, or worse. As a result you have some progressives who seek some sort of pure, race-neutral alleged class politics that supposedly will unite the dispossessed against the elite and will not confuse them with dirty matters such as race and gender.”

Elsewhere Fletcher, writing with Bob Wing, added: “Unity against neoliberal globalization will not come from ignoring race and gender disparities, but instead by working together to overcome them.”

Like the immigrant rights debate I encountered in the labor movement, many issues that might be disparaged as “identity politics” in fact are in no way separate from economics. They are enmeshed with it. The sooner we recognize that, the stronger our movements will be

Personal Growth Around Race and Class

The learning process is something you can incite. Literally incite. Like a riot.

Audre Lorde

I believe that one reason why debates about “identity politics” flare up – and why questions of addressing race and class are treated as divergent priorities – is that commentators in online forums or on social media commonly put forth broad proclamations that engage the issue on an abstract or analytical level, but that fail to account for personal experience, unconscious bias, or multiple ways of knowing. I believe that instead we must see how the interrelation of race and class manifests in our own lives and how it connects with our inner work.

In my own experience, I’ve found that there are still constant opportunities for personal growth and evolution. My process of coming to a new understanding of the importance of race is by no means complete. But it’s not always easy to be hit in the face with this fact.

One recent moment of personal growth came for me as I was attending a 2016 conference held by Race Forward, an institute whose work emphasizes issues of race and social change. The conference took place in the immediate aftermath of the November 2016 election. Like many others, I was shell-shocked by the results. With Donald Trump’s rise, openly racist and Islamophobic actions were flaring up around the country. But conversations at the conference highlighted not only this blatant, overt bigotry, but the more subtle manifestations of racism as well.

My Black colleagues shared experiences about how inescapable the reality of race was in their daily lives: “When you’re Black, you never get to turn off anything,” one participant told me, “you never get to disguise who and what you are. You’re seen as Black first.” A friend, who is Black, shared memories of how, when she was growing up, she would be praised by White adults for being bright and articulate, as if this were a surprise, while her White peers who were also good students were treated differently, praised for specific accomplishments and for meeting higher standards.

During discussions at the conference of slavery’s impacts, I felt the weight of generations of trauma. Of course, I had been aware of the prominent role of slavery in American history. Yet, as a White person, I could afford to see this as something that resided in the distant past. Listening to my Black colleagues, I realized that they had no such luxury. The legal and social codes once used to enshrine the dominance of a White, male class of slaveowners lingered persistently for generations, and the vestiges of slavery have wrought havoc on Black families, identities, economic security, and social mobility.

In my own inner work as a Jewish woman, I had come to recognize how living under oppressive conditions and being forced to migrate had created traits and behaviors in my family that carried from my grandparents, to my parent, and even, to some extent, to me. And so, at least in a limited way, I could appreciate how processing the trauma of racism would be no quick and easy process—particularly when the evidence of bias and inequality remains embedded in our schools, our neighborhoods, our economy, and our legal system.

It wasn’t that I hadn’t considered any of these subjects before. It’s that I could choose when to think about race, and when to move on to other concerns. As my colleague had put it, I could turn it off. Or so I thought.

This illusion, that race is part-time, that it is somehow an optional part of one’s identity, is a defining feature of White privilege. And coming to a fuller realization of this changed the way I think of myself as a racialized being. I began to gain a deeper awareness of my Whiteness, of feeling myself as a part of a group that I had not chosen to be a part of, but that nevertheless has shaped my lived experience.

As a White person, making an admission that I still have far to go in my evolution around race is a scary thing. Many of us are desperate to prove that we are free from racism and could not possibly harbor any discriminatory animus. Because of this, even acknowledging the reality of race in our society—looking beyond the myth of colorblindness—can be personally threatening for many White people. To acknowledge that we might be the beneficiaries of racist structures or that we might have been affected by living in a racially inequitable society threatens to implicate us in a system that we abhor. For those of us who see ourselves fighting for a vision of a multiracial and economically just society, acknowledging our Whiteness can feel like an affront to cherished ideals.

Yet I now believe that owning Whiteness is a crucial part of addressing racism. Even as I remain committed to economic justice — and to pushing for fairer, more equitable labor relations within a system of racialized neoliberal capitalism — I believe that such campaigns must be coupled with interpersonal work to recognize and combat White privilege. For me, that means talking with other White people openly about race.

Race is one of the hardest things in America to talk about. I know from experience that the first reaction of many White people can be defensiveness; and I can relate to this, because I know that I, too, have felt defensive at times. As White people, we need to build stamina through inner work so that we can lean into discomfort and take on difficult conversations. We need to build a common language – incorporating concepts such as structural racism, white privilege, unconscious bias, and the construction of “Whiteness” – that allow us to talk about racism in a way which recognizes that no one escapes the impact of being socialized in our White supremacist culture. Finally, we can’t be afraid of making mistakes, but instead must engage with honesty and authenticity.

Of course, engaging in these conversations is not the endpoint. We must combine reflection and personal growth with a renewed commitment to organizing and public struggle. As White people, we must join in movements against immigration bans and police abuses, workplace discrimination and educational segregation–not out of a sense of charity, but coming from a place of solidarity. This means understanding our own stake in struggle to overcome White supremacy.

Learning how issues of race and class in America are inseparable has been a long process for me, and one that still continues. But I am convinced that it is essential — not simply as a strategic consideration in our efforts to win justice for workers in our economy, but as part of a wider struggle to affirm the humanity and secure the liberation of all people.

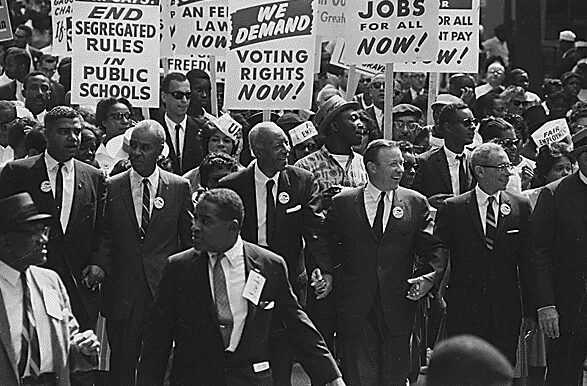

Banner photo credit: Rowland Scherman for USIA, wiobyrne | Public Domain

Thank you so much for just being honest about the difficulty you face while remaining committed to making things better. I’m firmly convinced that race versus class is a false choice as a black man and a factory worker.