“Disability is an invitation to relationship…It’s that opening that creates the whole ecosystem.”

– Sophie Strand

“Poetry is the language of the apocalypse.”

– Bayo Akomolafe1

As the newest members of turtle island, two-leggeds have always relied on ceremony for connection with, and for instruction from, older forms of sentience and the divine. Ceremonies are an essential part of all cultures across time. It is the absence of such sacred practices that results in disharmony, imbalance, and collective dis-ease. But what ceremonies and by and for whom? As social justice practitioners who come from a broad range of communities, cultures, and traditions, we often have few, if any, shared approaches for bringing together people, place, and spirit. This challenge has only been compounded during the pandemic, which has shifted so much of our work to a video screen.

While there are a number of rituals—often used by social justice practitioners—to help people connect across the virtual landscape, these tend to have more intellectual and emotional dimensions than spiritual. The increasing attention to somatic practices is expanding how we engage with one another in healthy and embodied ways, but our connection to the sacred, to sentience in its myriad of forms, to place—whether it be turtle island as a whole or a particular place on the carapace of her shell—is largely absent in our cross-cultural social change work. And it is this absence of ceremony that is impeding our ability to radically transform, as people and as a complex and interdependent ecosystem as a whole.

Members of the Change Elemental team and many others have written about the importance of inner work, of attending to the interiority of the intervener. But this work is often done separately, as individuals, or in our own spiritual communities, and not centered as much in our collective change efforts. There are exceptions of course, but these only make more stark the general absence of collective practices.

What is needed, what has always been needed, for transformational change, is ceremony—ceremonies in which we reconnect deeply with each other, with great spirit, with all of creation. In God is Red, Vine Deloria, Jr. describes the importance of ceremony for Native peoples. “The task of the tribal religion, if such a religion could be said to have a task, is to determine the proper relationship that the people of the tribe must have with other living things…” As all of creation is sentient—lizards, rocks, trees—then proper relationship is necessary with everything. And how that relationship is learned, celebrated, and restored, is through ceremony.

The healing of injustices and the restoration of aki, of the earth—including all of the creatures who depend on her and on whom she depends—requires restoring indigeneity—that is a deep connection to place, to its sacredness and interdependencies, to cultural sensibilities that are shaped by these.2 This is an individual, collective, and planetary necessity. The restoration of indigeneity requires reconnecting to indigenous practices, whether those practices are indigenous to the Americas, Africa, Asia, or Europe. For those who are not connected or actively reconnecting, this then is your task—and yes, it can be complicated, painful, and messy. It is an extension of inner work, of cultivating the ability to be present to what is and was and then draw on this ability to help create what will be.

And too, when we come together as change makers, we must hybridize and invent new ceremonies to support our current collection of igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic beings—all while centering the primacy of the indigenous world in which we are currently walking. It is a potent task, but not without antecedents.

The evolution, resistance, and resilience of indigenous spirituality in the face of settler colonialism and the middle passage provide some clues for how we might accomplish such transgressive divination. And while these adaptations were the result of subjugation and duress, our current times—the extraordinary amount of injustices we are quite literally buried in—necessitate another sacred leap in order for us to work collectively together.

So, how do a diverse group of social justice practitioners develop and practice ceremonies together? One answer can be found in Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer:

I knew that in the long-ago times our people raised their thanks in morning songs, in prayer, and the offering of sacred tobacco. But at that time in our family history, we didn’t have sacred tobacco and we didn’t know the songs—they’d been taken away from my grandfather at the doors of the boarding school. But history moves in a circle and here we were, the next generation, back to the loon-filled lakes of our ancestors, back to canoes…. When I first heard in Oklahoma the sending of thanks to the four directions at the sunrise lodge—the offering in the old language of the sacred tobacco…the language was different but the heart was the same…. It was in the presence of the ancient ceremonies that I understood that our coffee offering was not secondhand, it was ours…. That, I think, is the power of ceremony: it marries the mundane with the sacred. The water turns to wine, the coffee to a prayer. The material and the spiritual mingle like grounds mingled with humus, transformed like steam rising from a mug into the morning mist.3

We find ceremony and we create it together. The languages may be different but the heart is the same. And in that collective mingling, we weave relationships with ourselves and each other, with spirit, and with all other sentient beings.

Learning the grammar of animacy [and here this means recognizing the sentience and aliveness of “things”] … reminds us of the capacity of others as teachers, as holders of knowledge, and as guides. Imagine walking through a richly inhabited world of Birch people, Bear people, Rock people, beings we think of and therefore speak of as persons worthy of our respect, of inclusion in a peopled world….imagine the possibilities. Imagine the access we would have to different perspectives, the things we might see through other eyes, and the wisdom that surrounds us. We don’t have to figure out everything by ourselves: there are intelligences other than our own, and teachers all around us.4

We are living in places flush with sentience. Whether we are working together in person and are able to root into the same soil and arc into the same sky, or we are connecting virtually from across the continent, we can be present to place, to plant and animal teachers, to the places and wisdom of our ancestors, as well as to the divine. In either circumstance, what matters is this presencing of sacred relationship, that we make our interconnectivity the space from which we do our social justice work. Not for reasons of emotional stability or creativity—although it does support both—because the problems we are trying to solve cannot be solved by human beings alone. Both Albert Einstein and Audre Lorde have told us this in different words. Einstein informed us that, “you cannot solve a problem with the same mind that created it.” And Lorde located this understanding alongside its concomitant history when she wrote, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Human beings do not, in isolation, have the ability to solve the problems we have created. A recent example of this can be seen by the effect a simple virus—one of the oldest life forms on the planet—has had on every nation across the globe. The response to this virus has been utterly human-centric, and in the US, utterly middle-class, housed, professionalized worker, and male-centric. And it has been to the peril of every social system, which by their design for and maintenance of inequities then resulted in cataclysmic harm to Black, indigenous, brown, immigrant, female-identified, disabled, refugee, poor—the list is endless—communities across the world. All of creation, whether we look to the big bang or to sky woman falling5, teaches us that we are wildly connected and interdependent, and without our devoted attention to this truth, we will, and do, continue to find ourselves tilting precariously over the edge of a cliff.

The way we presence this connection, the way we center its fundamental truth, is through ceremony. Ceremonies born of our disabilities, our differently-abled abilities, which, as Sophie Strand says, create the opening that enables an entire ecosystem to unfold. This opening too is ceremony. Ceremony is the poetry that languages a new way of being and ways of doing such that the apocalypse can utter its death rattle, be composted, and make way for the regenerative growth of the post-apocalyptic, indigenized, recombinant world in which all of creation can face one another, bow, and begin the dance anew.

1Quotes from their shared talk “New Gods at the End of the World” hosted by Science and Nonduality (SAND)

2“Indigeneity assumes a spiritual interconnectedness between all creations, their right to exist and the value of their contributions to the larger whole.” LaDonna Harris, Founder and President of Americans for Indian Opportunity

3Kimmerer, Robin Wall. “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants.” Milkweed Editions. Minneapolis, MN. 2013. Pg. 36-38

4 Kimmerer, Robin Wall. “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants.” Milkweed Editions. Minneapolis, MN. 2013. Pg. 58.

5 There are many written versions of this creation story. One of my favorites is `“You’ll Never Believe What Happened” is Always a Great Way to Start’ by Thomas King from his collection The Truth About Stories, House of Anansi Press, Inc. Toronto, Ontario. 2003.

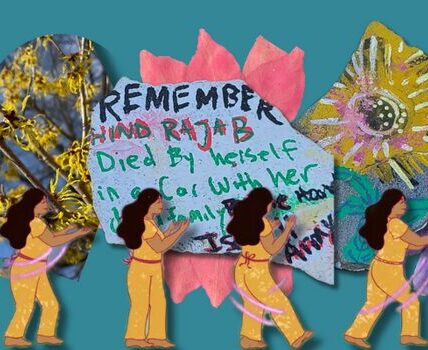

Header image credit: Taylor Wright